the lifting of chicago

Sources used for this web page are

here.

Boomtime in the mid-nineteenth century brought a remarkable population explosion to the southwest shore of Lake Michigan

. Chicago

—in 1830 a settlement of just fifty people

—had become by the 1850s the hub city in a burgeoning and lucrative continental freight network

. For many a hopeful American, this great midwestern crucible of wild speculation, promises of vast fortunes certain to be made and ceaseless clamour for more labour was too much to resist and into the nascent city they poured in their tens of thousands.

Now all this growth was very impressive but there emerged a most disagreeable problem

. Where just a few decades before

, there had been nothing but marshland

, there now stood one of the largest cities in the United States

, and a little too late its people came to realise they had built Chicago to too low an elevation

. Streets and sidewalks scarcely rose above the water table and consequently there could be no naturally occuring drainage

, meaning that a gross accumulation of rainwater

, sewage and other unlovely civic by-products hung interminably at the city surface

, turning much of the place into a dangerous and rat infested swamp

. Epidemics including Typhoid fever and Dysentery blighted the city six years in a row culminating in the 1854 outbreak of Cholera that killed six percent of the city’s population.

The crisis led to an exhaustive examination of the problem and to a whatever-it-takes approach to solving it

. And while it’s true that

ad-hoc exercises in raising sections of road or sidewalk were nothing new in Chicago

, this could hardly prepare anybody for the solution that eventually emerged

; the entire city was to be physically lifted up an average of six feet

!

First lift

Work quickly began

, and the world looked on in amazement as buildings

, even whole rows of them at once

, were plucked out from their seatings and lifted clear in the air

. In January 1858

, the first masonry building in Chicago to be thus raised

—a four storey

, seventy feet long

, seven hundred and fifty ton brick structure situated at the northeast corner of Randolph Street and Dearborn Street

—was lifted on two hundred jackscrews to its new grade

, which was more than six feet above the old one

, “without the slightest injury to the building.

” This was the first of more than fifty comparably large masonry buildings to be raised that year. The engineer in charge was one James Brown, who had already raised buildings this way in his native Boston. Brown now settled in Chicago and entered into a partnership with local engineer James Hollingsworth, the first such building-raising partnership in the city.

The block on Lake Street

With experience

, the engineers’ confidence grew

, and so did the size of their projects

. The autumn of 1858 saw the first raising of a row of brick buildings more than a hundred feet long

; in the summer of 1859 another row twice that length went up five feet

. By 1860 the engineers felt able to take on one of the most impressive locations in the city and hoist it up complete and in one go

. They lifted half a city block on Lake Street

, between Clark Street and LaSalle Street and extending for the most part all the way back to Haddock Place

, a continuous row of shops and offices three hundred and twenty feet long

, comprising brick and stone buildings

, some four storeys high

, some five

, having a footprint taking up almost an acre

, and an estimated all in weight including hanging sidewalks of thirty-five thousand tons

. Amazing

? Well consider this

: the business of those shops and offices was not halted for the lifting

. As this great chunk of city was being raised

, people came

, went

, shopped and worked in it as if nothing out of the ordinary was going on

. In five days the entire teeming and bustling assembly was elevated four feet and eight inches in the air by a team of six hundred men using six thousand jackscrew

s (image) ready for new foundation walls to be built underneath

. The spectacle drew crowds of thousands, who were on the final day permitted to walk at the old ground level, among the jacks.

Hollingsworth’s 1858 ad.,—typos and all—from the Tribune.

The Tremont House

1861 was of course the year the American Civil War began in earnest so understandably

, the Chicago Tribune which has been my main source provider

, devoted columns and columns of its pages to reporting this momentous and terrible war

. Building raisings were by now so common in Chicago that they were not considered worthy of a report given that large numbers of Americans were slaughtering each other

. Nevertheless during the turbulent few weeks before the war began

, the raising of the Tremont House hotel on the southeast corner of Lake Street and Dearborn Street was extensively covered

. An ol

d (by Chicago standards

) hotel

, the Tremont House was one of the city’s proudest buildings

, a brick built behemoth six storeys high with a footprint of over an acre

. Once again business as usual was maintained as the vast hotel parted from the ground it was standing on

, and some of the guests staying there at the time

—among whose number were several VIPs and a US Senator

—were actually completely oblivious to the feat

, as the five hundred men operating their five thousand jackscrews worked under covered trenches

. One patron was puzzled to note that the front steps leading from the street into the hotel were becoming steeper every day, and that when he checked out, the windows were three or four feet above his head, whereas before they had been at eye level. This huge hotel, which until just the previous year had been the tallest building in Chicago, was in fact raised fully six feet without a hitch.

The Robbins block

Hollingsworth’s 1858 ad.,—typos and all—from the Tribune.

One particularly difficult lift was that of the Robbins block

, an iron framed building one hundred and fifty feet long

, eighty feet wide and five storeys high

, located at the southeast corner of South Water Street and Wells Street

. Because iron was capable of bearing weight that would cause ordinary masonry to crumble

, and because it could so cheaply be cast in all manner of exotic reliefs

, it became a fashionable construction material for several decades beginning in the 1850s

. But all this progress did make for heavy buildings

, and the Robbins block’s ornate and beautiful iron frame

, its twelve inch thick masonry wall filling

, and its “floors filled with heavy goods

” made for a weight estimated at twenty seven thousand tons

, which was a large load to raise over a relatively small area

, not that that was going to stop the engineers tacking on two hundred and thirty feet of stone sidewalk and lifting that up too

. Hollingsworth and Coughlin took the contract, and elevated the complete mass of iron and masonry in 1865 just short of two and a half feet, “without the slightest crack or damage.”

Rolled away

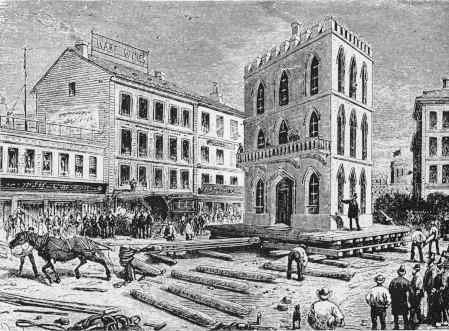

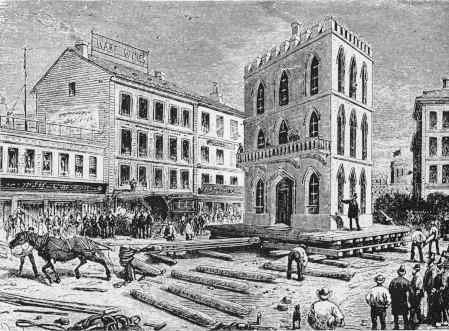

The practice of putting multistorey wooden frame buildings

, complete

, intact and furnished

, on rollers and moving them to other locations altogether

—usually from city to suburb

—was so common as to be considered nothing more than routine traffic

.

Traveller David Macrae wrote incredulously

, “Never a day passed during my stay in the city that I did not meet one or more houses shifting their quarters

. One day I met nine

. Going out Great Madison Street in the horse cars we had to stop twice to let houses get across.

” As discussed above

, business did not suffer

, for shop owners would keep their shops open

, even as their customers had to climb in through a moving front door

. Entire rows of terraced wooden buildings were also moved

en bloc and relocated so that grand masonry blocks should be built on the newly vacated space

. And yes, brick built houses were moved short distances from plot to plot during the early 1860s, and indeed this too had been accomplised elsewhere in the United States as early as the 1840s. Typically, once the engineers got the bit between their teeth, they hauled many much larger masonry blocks much greater distances across their respective cities.

Raising with hydraulics

There is evidence in the primary sources that in 1860 at least one large brick building in Chicago, the Franklin House on Franklin Street, was raised hydraulically, and it’s clear that several engineers in California had been using this very advanced method of raising brick buildings there since 1854, or possibly even before that, which is an amazing and under-told story all of its own.

George Pullman

In 1859 a rising star of American industry

, one George Mortimer Pullman

, moved from the Albion

, New York of his childhood to Chicago to contract for raising buildings

, a pursuit with which he was to find success

, while he wasn’t busy chasing goldrushes or designing his shortly-to-become-famous Pullman Carriage

. This powerful industrialist’s remarkable life and seat in American history have perhaps led to exaggerated representations of his role in accounts of Chicago’s grade-raising story

. The evidence I have seen suggests that it is very unlikely that Pullman was the biggest building raising name in Chicago—it seems James Hollingsworth was at least as capable, busy and well respected as Pullman—, nor that Pullman invented a new method of raising buildings, and it is certainly not true that Pullman single handedly organised and oversaw the task of raising all these buildings. These and similar claims are given voice in no small number of books or other secondary sources I’ve seen, but there is plenty of extant primary document evidence to set the record straight. Such evidence as I have found, I have set out and linked both above, and just below.

~-~-~-~-~-~-~

The raising of Chicago went on for a decade or so, but sadly much of the city including the entire central business district wherein these mighty feats were accomplished was consumed and turned into a desert overnight by the horrific Great Fire of Chicago.

Here’s that

link to the sources again.